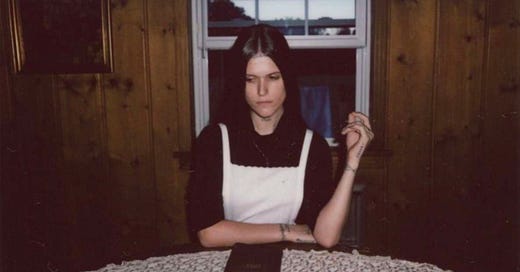

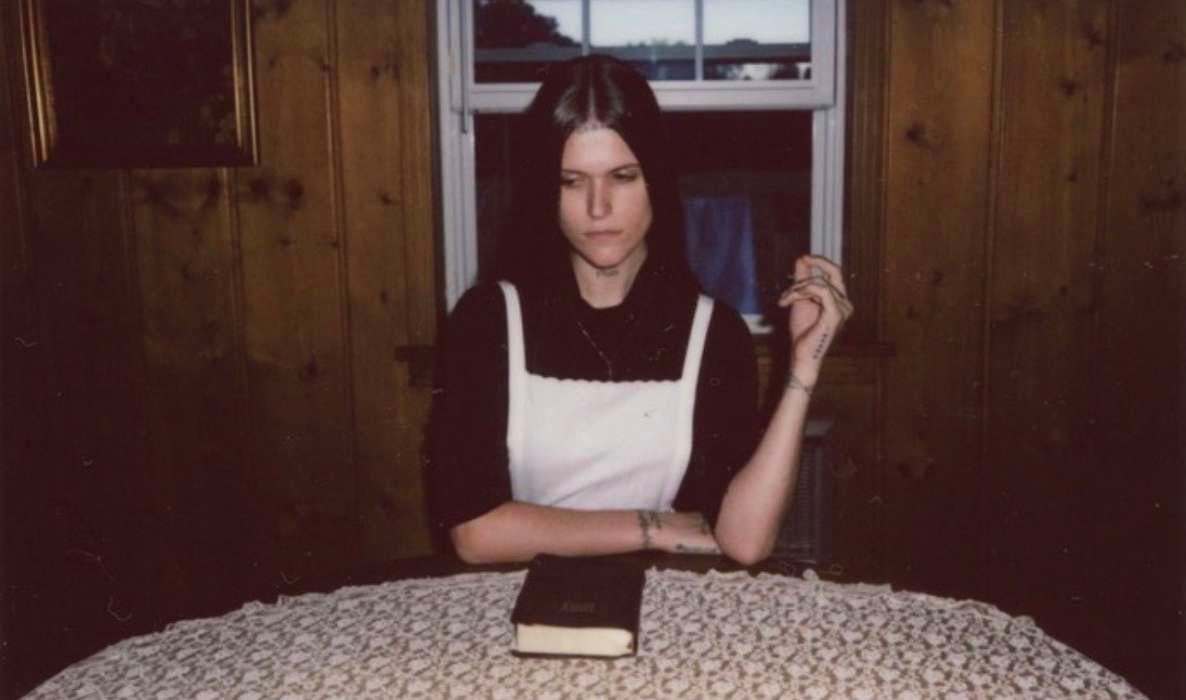

Feel Song 19: Strangers - Ethel Cain

Ethel Cain, generational trauma, the sacred and the profane.

Dear listener,

What is the cost of intergenerational and childhood trauma? What is the cost when that is combined with gender-based violence? It costs us our very life, this life, that we have to spend unpacking that shit that was given to us.

These days I have been mainly listening to two albums on repeat: Lana Del Rey’s Norman Fucking Rockwell and Ethel Cain’s Preacher’s Daughter. Both were released years ago and I had not thought much of them when they first released. But like a switch, I had listened to them again and understood completely. This happens with me sometimes. I wonder what had to happen in my life for me to finally enter the emotional territory of certain albums.

Both Lana and Ethel Cain are consciously fashioned personas (their real names are Elizabeth and Hayden respectively) for art that, while different, are similarly grounded in Americana, an aestheticised expression of ultimately difficult and even traumatic aspects of girlhood and womanhood, and a kind of sensuous sexuality that is undeniably located in a world of patriarchal violence. I do think the last point is an important one and manifests differently between the two musicians. But for today, I want to talk about Ethel Cain whose aesthetic has been dubbed as ‘Southern Gothic.’ I’m no expert, but think: american midwest, houses built with wood with pale flowery wallpaper, small towns people dream of leaving, the working class, and church-going conservative white christians.

Some of the themes that surface when listening to Ethel Cain include intergenerational, childhood, and religious trauma, family and domestic violence, abuse, poverty, and being attracted to men that are bad for us. Sounds heavy, but this list doesn’t even begin to fully capture things. In an interview, she shares:“I’m deeply engrossed in the idea of generational trauma and skeletons in closets. ‘The sins of the father’ and all that. It’s where ‘Daughters of Cain’ came from in the first place. The idea that something your great-great-grandfather did 100 years ago can still fuck you up; those deeply rooted issues in your family that never get resolved and are just further inbred into your bloodline with each generation, twisting and turning and contorting until it rips you all apart.”

She’s talking about generational trauma on a scale that is so deep and extensive that it requires a language that stretches into the realm of the mythic. And for a woman that grew up as the daughter of a deacon and spent her sundays in church, it makes sense that biblical imagery and language is used.

What undeniably captivates me about Ethel Cain is how heavily suffused her songs are with not only the religious, but also its desecration and the profane. I’m not fully inducted into the Daughters of Cain fan-cult nor am I fully educated on the full lore of her album, but some fan theories even included mentions of murder and cannibalism. The deepest, most profane possibilities of human action are not locked away, they are exorcised in order for real release. The spiritual and ecstatic stretches into the taboo then back again into rapture. Ethel Cain could write Erotism but Georges Bataille could not write Preacher’s Daughter.

There is so much to unpack about the album, and the religious themes interest me very much. And though I have experienced religious trauma (which religious woman hasn’t), I’m no theologian and I only have your attention for so long. What I am is a woman with daddy issues so let’s talk about that theme instead.

The song I bring to you is ‘Strangers,’ my current favourite in Preacher’s Daughter and the final song in the album. In Preacher’s Daughter, a narrative follows the character of Ethel Cain as she falls in love with a man named Isaiah, is emotionally and literally trapped and abused by him, and finally murdered. By the final song Strangers, she is saying goodbye with the final lines being: “Mama, just know that I love you (I do) / And I'll see you when you get here."

Who is Ethel Cain? As I listen to the album, she strikes me as a woman who grew up in a home where her understanding of love was twisted and conditional. The kind of deprived childhood and adolescence that twists affection to create a people-pleasing woman anxious and desperate to feel loved and vulnerable to predatory men who desire a person least likely to challenge them and their egoes. It is often said that such women attract bad men, but I think it’s the other way round. It is predatory men that actively seek out the women whose boundaries have been distorted and who want nothing more than to unconditionally pour love with the desire that it would be reciprocated.

When one’s boundaries have been distorted, you’d do anything for your man in order not to lose him and his pathetic crumbs of approval that is mistaken for love. In ‘Strangers’ we hear Ethel sing: “I tried to be good, am I no good? / Am I no good? Am I no good?” and “I just wanted to be yours, can I be yours? / Can I be yours? Just tell me I'm yours.” She seems to know that this grovelling is wretched. Her desperation to be loved is an uncomfortable mirror to her abuser and she asks Do I make you feel sick? A line that repeats in the song unto its culmination.

What did Ethel Cain do? Some fans said she even gave up her faith, the ultimate taboo for the religious. But the last line of the song seems to suggest otherwise, as she shares that she will wait for her mother on the other side. Where else would she speak with such grace, love, and forgiveness except in the cradle of the creator?

And yes, it pains me to say there is forgiveness in the final song of this album despite the narrative arc that ends with the murder of an abused woman. Before she bids us goodbye, Ethel says to Isaiah: I never blamed you for loving me the way that you did / While you were torn apart / I would still wait with you there.

There’s a line I always hated hearing when I was being gaslighted by a man who always dismissed my anger at racists and sexists: “hurt people hurt people.” Even as I was the one who was hurt and wronged, I was asked to sympathise with the perpetators of bigotry. I was being told that I was the one perpetrating harm for not being able to account for whatever trauma in their lives that made them that way. I was not a person worthy of being sympathised with, I was just a vessel from which empathy could be drained for everybody else. But I had yet to fully stand in my own power and to fully understand boundaries and real love (not talking about romantic love here). At that time, I still began with the charge that the first deficient thing in any conflict was me. This is the most boring story ever, because it’s common as hell.

Ethel forgiving Isaiah makes me think of that. She might have supposedly abandoned her faith for her man, but she didn’t, really. She is still the naive and innocent person who wanted love with a man who never had interest for it in the first place. In a world where narratives of female empowerment mean seeing girlbosses, victory over abusers and perpetrators, and neat resolutions where women stand powerful and self-assured, it can feel disappointing to find a narrative where a woman ‘loses’. There is no neat resolution here. I think of the 1988 French drama film directed by Claude Chabrol Story of Woman, that ends with the death sentence of a woman who was giving abortions at a time when the procedure is banned. It was based on the true story of Marie-Louise Giraud, guillotined on 30 July 1943. It was a film that moved me so deeply, and reflected the reality and banality of female violence and despair. There is no neat resolution there either.

In Preacher’s Daughter, Isaiah is a murderer. But in the holy texts, he is a prophet who was martyred, murdered in gruesome circumstances, but whose promises of a coming messiah welcomes hope, redemption, and healing after a time of suffering and tribulation. What to make of this subversion? Maybe the fact that abusers can be adept at appearing like a promise, a redemption, and a source of love, only to later to reveal themselves as the opposite. The martyr in Preacher’s Daughter is not the namesake of the prophet, it is Ethel. Blessed are the meek.

Through the mythic, the religious, the profance, Ethel tells us the terrifying truth. The world wants to comfort us with images of victory and illusions of liberation. But reality is different. Terror still resides here.

What is the cost of intergenerational and childhood trauma? What is the cost when that is combined with gender-based violence? It costs us our very life. Before you traumatise your girls with ideologies that only know of punishment and limitation, think of the emotional life of the woman she will become. Think of the fate that you invite for her. No woman deserves the fate of Ethel Cain, who knew liberation only in heaven.

With love,

D